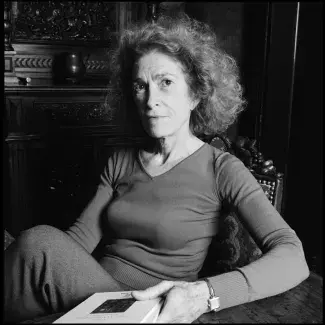

Tribute to Mirelle Delmas-Marty and excerpts from her thoughts on digital technology

Eminent French jurist and academic, Mireille Delmas-Marty, sadly passed away on Saturday the 12th of February at the age of 80. It is with deep sadness that the Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne community pays tribute to her by compiling below some extracts of her thoughts on digital technology.

Official tribute from the Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne University

Mireille Delmas-Marty was a professor at the “Collège de France” between 2002 and 2012 and became a member of the “Académie des sciences morales et politiques” in 2007. Notably, Mireille Delmas-Marty taught at the University of Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne from 1990 to 2002 and founded the “l’Institut des sciences juridiques et philosophie de la Sorbonne” (“ISJPS”) in 1997. Mireille Delmas-Marty was also an honorary doctor of eight universities around the world.

Christine Neau-Leduc, President of the University of Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, opined that "the name of this exceptional jurist will remain forever attached to the University of Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne where she was a professor from 1990 to 2002".

During the course of her lifetime, Mireille Delmas-Marty taught in numerous universities around the world including Bangui (1978), Sao Paolo (1980), Maracaibo, Montreal (1983), Brussels (1997) and Florence (Academy of European Law 1997 and European University Institute 2001-2002). Mireille Delmas-Marty was also a visiting Professor at the University of Cambridge in 1998.

Member of the National Consultative Ethics Committee from 2003 to 2008, Mireille Delmas-Marty was subsequently elected to replace Jean Cazeneuve as President of the "morality and sociology" section within the Académie des sciences morales et politiques in 2007.

In 2011, Mireille Delmas-Marty was appointed by the Socialist Party's High Authority to organise the elections designating a candidate for the head of a political party. Undoubtedly, Mireille Delmas-Marty lived a fulfilling life thanks to her hard work and determination. Mireille Delmas-Marty was a devoted human rights advocate and defended the concept of "sovereignty in solidarity" throughout her career. Notably, she sought to extend the notion of "sovereignty in solidarity" across the borders, emphasising the necessity to protect common goods, not only at a national level but also universally.

In 1971, Mireille Delmas-Marty’s first book, entitled “Le mariage et le divorce” (Marriage and divorce), was published by Presses Universitaires de France (PUF). She went onto publish approximately 20 individual works and participated in numerous other collective works. Her latest book, entitled “Sur les chemins d'un jus commune universalisable”, was published in 2021 by Mare & Martin and co-authored with Kathia Martin-Chenut and Camila Perruso. Mireille Delmas-Marty’s work was centred around the internationalisation of law, including human rights, economic, social and environmental rights. As a result of everything she has achieved during her life, Mireille Delmas-Marty will always remain a renowned academic and jurist.

Compilation of Mireille Delmas' thoughts on digital technology and artificial intelligence through the following selected extracts

- Extract from an interview on the Grand Continent "In the spiral of humanisms, a conversation between Mireille Delmas-Marty and Olivier Abel" (16 January 2021)

It is necessary to “choose freedom and responsibility, that is to say, a humanism of indeterminacy, which conditions our creativity and our responsibility. It is a difficult choice because it implies giving up what you call “overprotection”, which a small part of humanity benefits from, physically improved by biotechnology and increased in its cognitive capacities by artificial intelligence. If it responds to the catastrophic story of the collapse, through the adventure of globalisation rather than through the Chinese approach of the “New Silk Roads”, this choice “deprotects” us. To use your neologism, we have become accustomed to excessive “productivism and consumerism” and we must give this up. Through observing millions of individual data accumulated by social networks and billions of conversations recorded by intelligence agencies, democracies are already transforming themselves into a form of totalitarianism. This is frightening because it exploits our overwhelming desire to have access to everything, all the time, without having to wait. We are “driven by narcissistic impulses even more powerful than sex or food as we move from one platform and digital device to another, like a rat in Skinner’s box, who by pushing buttons, desperately seeks to be more and more stimulated and satisfied”.

- Extract from the article "Between the doldrums and autopilot, can the law guide us towards a peaceful globality? - Study by Mireille Delmas-Marty, member of the Institute and an emeritus professor at the Collège de France", La Semaine Juridique General Edition n° 14, 2 April 2018, doctr. 403.

“It is still possible that everything conforms to norms influenced by a profound and radical change caused by digital technologies and the emergence of a new cooperative, horizontal model imposing its own norms. Sometimes described as a "cooperative mesh mode in organised systems at the expense of the hierarchical mode", the digital or “super numerical” society distinguishes itself from linear and pyramid structures but also from the organised “tree” and “star” networks. These “mesh” networks, that use big data accumulated by the “digital revolution”, have the vocation to cooperate between themselves, like cities or so called “intelligent objects” without the need for prior programming, because cooperation is written within the system itself. In the long term, the objectives will no longer be defined in advance but will be automatically created by interactions between systems, humans and various techniques. The risk then arises that, by transforming the spirit of cooperation into cooperation without a spirit, dehumanisation will occur through the loss of breath and therefore of meaning. In autopilot, the driver may advance forward but is unable to choose the direction. The replacement of both the pilot and captain would end up diluting all other norms. In conclusion, one can hope that the recomposition will be quicker than the decomposition of the existing order, that will lead to the dilution of law, indeed its dissolution, in the large ocean of globalisation. A real race is now underway to find a common law that would combine the rule, which is interactive and evolving, and the spirit of the rule, which is humanistic and pluralist. Would the implementation of an ideal grammar in the framework of governance shared between the actors of the triangle of 'knowledge, desire and power', transform the globalisation of predators into a new story, one that has yet to be written, that of a peaceful globality? In any case, this is the challenge of a "universalisable" common law”.

- Extract from the course: Towards a community of values? - Fundamental human rights, "Etudes juridiques comparatives et internationalisation du droit" by Mireille Delmas-Marty, Collège de France, 2007.

"In order to resolve the practical questions concerning the new or renewed possibilities of selecting human beings by eugenics, producing human beings by cloning, or even manufacturing quasi-human beings ("humanoid" robots), the same difficulties in connection with crimes against humanity can be identified. The proposed response seems feasible and consists in defining the “value-humanity” (formed according to two processes of differentiation and integration). This notion consists of two elements: the singularity of each human being and his or her equal belonging to the same community.

In short, the refusal of dehumanisation, like the creation of human beings, at the heart of anthropogenesis, is centred around a single species and the differentiation of cultures that characterise humanisation.

In order to obtain the result evoked above, it is necessary to achieve a balance between anthropogenesis and humanisation, governing the universalism of the 'human/inhuman' couple. Failing that, Henri Atlan has already announced that "the debate on cloning will be revived when human ectogenesis [i.e. extracorporeal gestation in an artificial womb] becomes possible". He explains that the implantation in a natural uterus remains both a “benchmark as well as a hurdle”, making it possible to control the techniques and to restrict the eventual application of non-sexual reproduction including cloning and parthenogenesis. However, according to Henri Atlan, this technical and symbolic hurdle will be overcome as soon as ectogenesis becomes a common practice adopted by a significant proportion of women.

Additional hurdles will be overcome with the development of new technologies such as “the artificial man” and the possibility of hybrids of living beings and machines. There is therefore an urgent need to be in agreement of what a ‘human/inhuman” pair consists of.

The synthesis of anthropogenesis and humanisation suggested above challenges the concept of humanism. Humanism was traditionally seen as two opposing notions, that of nature and culture (including technologies). Other concerns have also been raised about the place of humans confronted not only with inhumans, but also with non-humans.

The human/non-human couple

One of the most obscure questions contained within 'human' rights, in their claim to universality, is to know where to place the human in relation to the non-human, regardless of whether that is an animal or the nature.

The human/non human couple is an anthropocentric, dualistic and separatist concept that has finally emerged and been adopted in Europe over the last few centuries. Philippe Descola calls it “naturalist” and distinguishes it from three other human / non human conceptions. She considers humans as “the only ones who possess the ability to be conscious yet, similarly to non-humans, they attach themselves to their material characteristics”.

In regards to the legal field, this model has arguably inspired international law, leading to the Universal Declaration of the irreducible human (article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) proclaiming that “all human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights”). However, it seems as if the current law is at the forefront of challenging the credibility of naturalism. Due to the combined effect of scientific discoveries and technological innovations, the resistance of ecological movement is becoming more radical. The credibility cemented within the foundations of the legal humanism of separatism concept are being shaken by a development promoting a renewal of legal humanism.

The questioning of the humanist credibility, founded upon two apparently contradictory movements, could lead to its demise. On the one hand, the very notion of legal humanism will be weakened, indeed threatened, by the adoption of a Declaration of Animal Rights (adopted at a UNESCO conference in 1978 and subsequently modified in 1989) that seems to base these rights on human rights. Indeed, the preamble states that "every living being has natural rights and every animal with a nervous system has distinctive rights". Article 8 goes so far as to define “genocide” as any act “jeopardising the survival of a wild species and any decision leading to such an act”.

However, on the other hand, humanity, extended to future generations, will find its prerogatives strengthened as an owner of heritage. Notably, the notion of the "common heritage of mankind", created during a conference on maritime law, has been included in several international conventions in order to determine certain natural spaces, such as the moon and other celestial bodies (1979 Convention) or the seabed (1982 Convention).

Torn between the personification of the animal and the patrimonialization of nature, the non-human is no longer clearly distinguishable from the human in this new conception of the world that seems to favour the monism of man. Yet, this is undoubtedly only a transitional model as these two movements remain incomplete.

The upheaval and a plethora of this concept could foreshadow the recompositioning of values, resulting in a new type of legal humanism that does not take the form of any of these four models. Instead, it takes the form of the four models merged together. The law continues to draw a distinction between the human and the non-human and thus, there is a certain dualism. However this dualism is attenuated by a progressively emerging link with anthropocentrism, whether that be in regards to an animal, perceived as a sentient being that can not be likened to a physical person nor a thing, or in regards to nature, which is considered to be a common good rather than a patrimony.

Philippe Descola suggested the “relative universalism” approach, in the literal sense, i.e relating to a relationship. This is the hypothesis that I would like to transpose in the legal field and explore as a possible progression of the legal humanism “of relationship”, which would build the relationship between humans and animals, and more broadly with nature. Consequently, the dualism that maintains a strict opposition between humans and non-humans and the continuity of monism, which is arguably excessive, will be avoided.

The more one questions the legal nature of the animal, the more the binary choice between dualism (animals and humans are two separate, distinctive things ) and monism (the animal is a person, comparable to a human) appears inadequate to account for an evolution that maintains a separation between the human and the non-human. Instead, it organises their relationship. Consequently, highlighting that the Charter was designed “for man and not for nature itself”, the promoters of the 2005 French Constitutional Charter for the Environment were determined to promote their ecological humanism approach. It remains to be seen what significance will be attributed to this approach. Certain commentators see it as confirmation of human-centred humanism. Nevertheless, the preamble also states that “man exerts an increasing influence over the conditions of life and his own evolution” and that “biological diversity, personal growth and the progress of human societies are affected by certain patterns of consumption or production and by the excessive exploitation of natural resources”. As a result, “the choices made to meet today’s needs should not compromise the ability of future generations and other people to meet their own needs”. As a consequence, a statement, which is relatively rare in constitutional matters, was made outlining the obligation that “everyone has a duty to participate in the conservation and improvement of the environment” (article 2). Whatever doubts there may be regarding its practical scope, this provision encourages a more autonomous protection of the environment, which is further reinforced by articles 3 (duty of prevention) and 5 (known as the precautionary principle, despite the fact that it prompts predictions instead).

Perhaps we have reached the limitations of the possibilities offered by the concept of “human” rights. Thus, lawyers should be encouraged to design a new type of relationship between humans and non humans, in order to put the law to use in the relationship between humans and other living species, rather than only utilising law to regulate the functioning of human society. The more radical approach consists in making biodiversity, in its own right, a subject of law and therefore recognising the intrinsic value of non-human life (Cf. the Constitution of the Swiss Confederation).

However, it seems to me that this intrinsic value is an illusion as it can not be defined and defended without the involvement of humans. In order to imagine what he has named "the parliament of things", Bruno Latour, borrowing from the “moderns” (the separation of nature and society); the “pre-moderns” (the inseparable things and signs) and the “post-moderns” (denaturalisation), turns towards another approach, that of “redistributed humanism” in which the human becomes a mediator.

I see this as an invitation to overcome the current unbalanced legal relationship, whether that consists of a right of the human over the non-human or the opposite, so that, in its relationship with the non-human, humanism replaces the bilateral form of a right with the unilateral form of a “duty”. Although this change has already been inscribed within numerous texts concerning both animals and nature, it is not sufficient enough to define a legal regime. In order to define a legal regime, we will attempt to explore the possibilities offered by the unfamiliar concept of “global good”, which refers simultaneously to the economy (collective good), politics (public good) and ethics (common good). Indeed, even this concept’s ambiguous nature could contribute to the formation of universal values”.

https://www.college-de-france.fr/media/mireille-delmas-marty/UPL27270_6_Activit_s_2007_2008_v3.pdf